Photography by Danny Fulgencio

Photography by Danny Fulgencio

It was May 21, 1994. The occasion was C. Gus Katsigris’ name day, and our small tour group had gathered in the courtyard of Katsigris’ birth home on the Greek Peloponnese peninsula. The evening was warm in Leonidion, and we were about to devour a groaning board of food to celebrate.

Here in North Texas, Katsigris is the face of the El Centro Food and Hospitality Services Institute, where a parade of chefs have streamed through its kitchens over the past 40-plus years, including Marc Cassel (20 Feet Seafood Joint, formerly of the Green Room), Jamie Sanford (Zanata), Dunia Borga (La Duni Restaurants), Helen Duran (culinary consultant and former Central Market cheese maven), Chad Houser (Café Momentum), Randall Copeland (Restaurant Ava and Boulevardier) to name a few. Katsigris, along with Dr. Frances Hitt, created El Centro’s program in 1970 nearly out of thin air.

“It wasn’t just a job [for him],” says Richard Chamberlain, a student from 1978-80 (Chamberlain’s Steak and Chop House and Chamberlain’s Fish Market Grill). “You could see the passion for the business come out in him… He is such a charismatic guy.” The institute remains the region’s most affordable, comprehensive curriculum. “It’s an awesome program,” says Michael Weinstein, a student from the early ’90s better known as the Dread Head Chef behind the highly successful line of dessert chips and salsa.

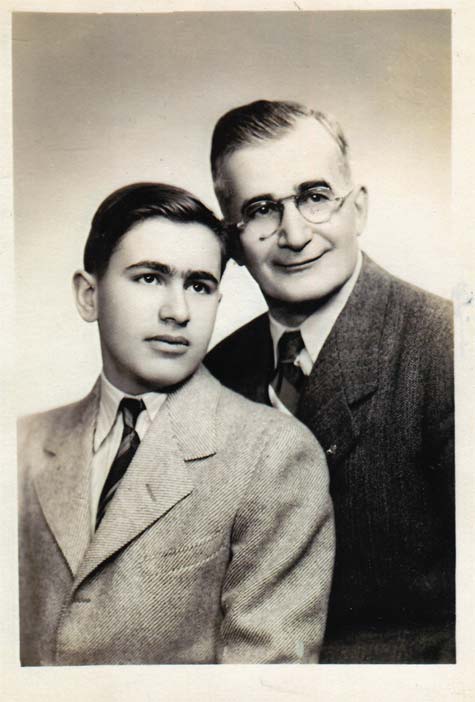

Gus with his father John Katsigris, 1947

Gus with his father John Katsigris, 1947

While overseeing El Centro’s program, Katsigris also found time to run a restaurant and work closely with the Texas Restaurant Association and the Greater Dallas Restaurant Association. “He knows so many people in the business,” says Weinstein, “and helped students get into apprentice positions.” In the classroom, Katsigris taught the nuts-and-bolts of running a restaurant. “I remember his class as being the most interesting,” says Chamberlain. “He would say, ‘Let’s cost out this plate.’ Oh, you count the butter? ‘Three cents.’ The sugar for the iced tea, you count that? There were times when he would get really angry, when kids weren’t taking it seriously. He’d turn red. Rant for a couple of minutes. Then get everyone back on track.”

Besides restaurants, the program reaches into hospitals, nursing homes, corporate kitchens, schools and supermarkets. More than 10,000 students attended his classes between 1967 and 2010. Twice, Katsigris has retired: from full-time faculty in 2001 and from adjunct faculty in 2005. But on any given day, as he nudges 80, you’re still likely to find him at the downtown campus, doing what he loves to do. “I’ve never met anyone who doesn’t like him,” says ’90s alum Janice Provost, now owner of the Oak Lawn bistro Parigi “He always remembers your name and where you work. He just has this passion for what he is doing and for the next generation. He is the true godfather of the culinary program.”

Backpedal to the courtyard in Greece. Your name day is a bigger deal than your birthday, and you celebrate the saint day whose name you bear. In Katsigris’ case, that’s Konstantinos, or Constantine, the first Roman emperor to recognize and legitimize Christianity at the beginning of the 4th century. The table that day was a locavore’s dream, with nearly everything grown or made within a few miles: oven-fresh rustic bread, olive oil, pastitsio, cucumber-and-tomato salad with red onions, feta cheese, olives, eggplant, zucchini, roasted chicken, red wine, oregano and other aromatic herbs.

The caretakers of Katsigris’ home, John and Joanne Saris, prepared the lavish banquet. “John raises his own goats and makes his own feta,” says Katsigris. “He makes olive oil from my olive field… There’s no comparison with the tomatoes I can get today and the ones I get in Leonidion.” We ate and drank into the night, toasting our hosts and their health repeatedly. The tours were a way for Katsigris to share his heritage with colleagues and friends and included many wonders of Greece—the Parthenon, Delphi, Crete, Santorini, Knossos, Hydra—as well as the journey to Leonidion, a bouncy, three-hour cab ride from Athens.

America is far distant from this village perched between mountains and sea, and Katsigris was just 13 when he traveled to the United States with his father in 1946. He spoke no English. “My father and I came,” says Katsigris, sitting at his kitchen table in North Dallas.

Gus at his restaurant Crackers with the traditional

Gus at his restaurant Crackers with the traditional

Greek feast of Pascha, celebrating Easter

“His wife and daughter stayed behind. My sister and my mom never came to the United States.” Not even to visit. This was the way things were done. When his father was 65 in 1956, he returned to Greece for good. But in 1946, the “men” sought their fortune in America. “Greece was in shambles, destroyed completely,” says Katsigris. Civil war raged from 1946 to 1949. While his father worked, the younger Katsigris lived with the American Female Guardian Society and Home for the Friendless, and his job was to get an education. “It was like a boarding school, but we went to public school,” he says. “I remember I adjusted quickly.” But the food sometimes took him aback. “I didn’t know what Brussels sprouts were, what turnips were. When they served fish without bones, I couldn’t figure that out.”

His father squirreled away enough cash to send his son to Columbia University, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in 1955 and a master’s in 1956. With the Cold War escalating, Katsigris joined the Air Force ROTC while at Columbia and entered the Air Force as a Second Lieutenant upon graduation. He was sent to Harlingen for flight training and on to Waco for F-89 Scorpion fighter training. In Waco, though, his commanders made an alarming discovery: “I could not fly the planes. I would puke,” he says. So the navigator became an instructor. In Waco, he also met his wife-to-be, Evelyn Colias, whose family owned the Elite Café, a historic landmark still operating today under different ownership. He and Evelyn married in 1961 and, after working briefly in Baltimore, Katsigris was called back to run the Elite Steak House, another of the family’s three restaurants. He had scant training. “I had washed dishes, bartended and helped cook in college,” he says.

The business flourished under his leadership from 1962 to 1970, but Katsigris itched to do something different. “I started commuting to [the University of Texas at] Austin to get my doctorate. One day the associate dean of the business school said, ‘What are you doing here?’ ‘I’m tired of the restaurant business,’ I said. ‘Have you thought about teaching?’ he said. ‘They’re opening a new college in Dallas. Why don’t you take a look?’”

Katsigris got an interview at El Centro Community College, but no job offer. But in the spring of 1970, then-president Donald Rippey called him back for another interview. Then another. The Restaurant Management and Culinary Arts program was in big trouble.

“The program was going to close,” Katsigris says. “It was either up or out.” Rippey hired Katsigris in the fall and gave him one year to revive the program.

You could say the rest is history. Katsigris started by offering night classes, and enrollment more than doubled. He and Dr. Hitt “designed the program that is essentially what it is today.” The Food Service Institute moved into the then-new Building C with expanded facilities in the mid-’70s. “It became the Food and Hospitality Institute in the early ’80s when we began offering hotel management courses,” says Katsigris, who points out that the times also contributed to the program’s success. “Liquor by the drink had just come in,” he says. “That’s what brought the hotels in.” Before the Texas Legislature authorized the sale of mixed drinks in 1971, patrons were required to bring their own spirits to what were then defined as “open saloons,” which sold set-ups. The new hotels and burgeoning restaurant scene needed competent staff. Then, too, El Centro College (which dropped Community from its name) was well-positioned just as the rise of modern American cuisine and the celebrity chef began in the late ’70s.

Katsigris also owned and operated Crackers restaurant in an old house on McKinney from 1976 to 1990 (with a 1987-88 hiatus). People assumed his students worked there, but he says he avoided this because it complicated the student-teacher relationship. He also wrote The Bar and Beverage Book (Wiley & Sons), a textbook in its fifth edition, and has another manuscript at the publisher.

Katsigris has left an indelible mark on North Texas restaurants and the region’s food service and hospitality industry. Unlike his father, he harbors no illusions about returning to live in Greece, although he still tries to get back to Leonidion each year. “I cannot accept the world view that most Greeks seem to have, although I love them. I guess ‘you cannot go back home again,’” he says, paraphrasing Thomas Wolfe. Perhaps not, after a lifetime in the United States and the elixir of making a difference in thousands of lives. “I keep coming back to El Centro because I continue to marvel at the diversity of the student body and what our program is doing to improve each individual’s life,” he says. “I am in love with our graduates who have achieved so much.” Writer Kim Pierce has known Gus Katsigris since 1970, when she also worked at El Centro College.

Bits and Bites, a fundraiser benefiting the El Centro Food & Hospitality Institute, will be held from 4-7pm on Sunday March 10.

KIM PIERCE is a Dallas freelance writer and editor who’s covered farmers markets and the locavore scene for some 30 years, including continuing coverage at The Dallas Morning News. She came by this passion writing about food, health, nutrition and wine. She and her partner nurture a backyard garden (no chickens – yet) and support local producers and those who grow foods sustainably. Back in the day, she co-authored The Phytopia Cookbook and more recently helped a team of writers win a 2014 International Association of Culinary Professionals Cookbook Award for The Oxford Encyclopedia for Food and Drink in America.