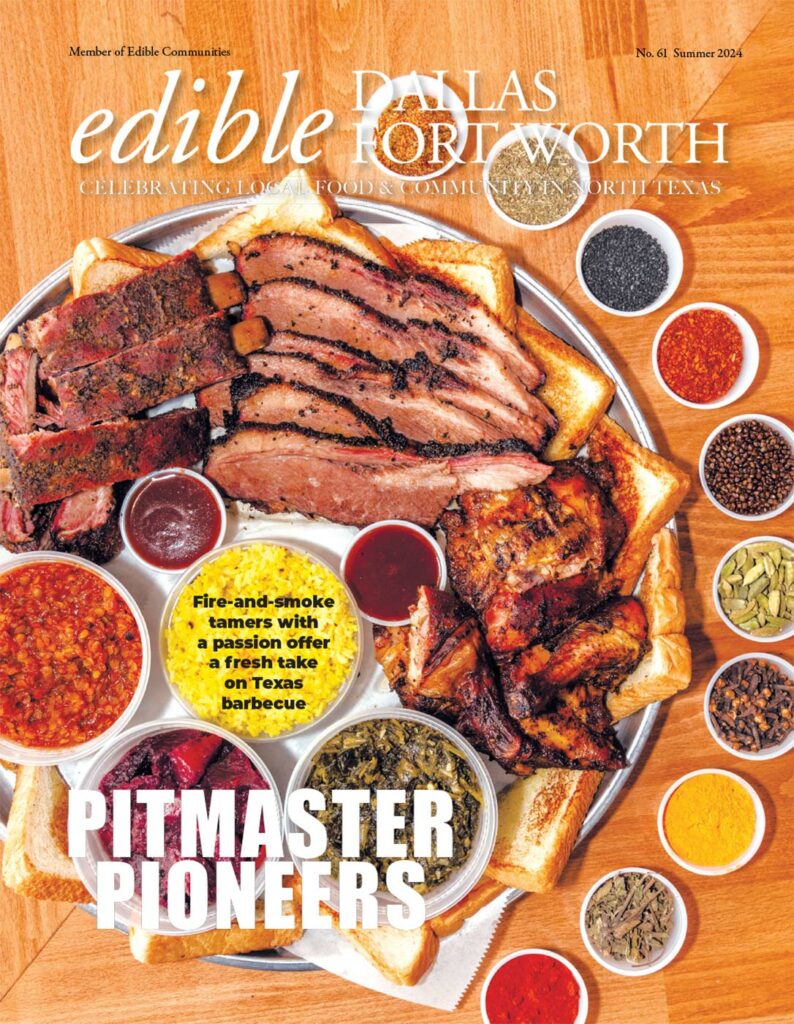

PHOTOGRAPHY BY MELINDA ORTLEY

PRAIRIE FARMSTEAD USES ANCIENT TRADITIONS TO REGENERATE THE SOIL AND THE RANCHING INDUSTRY

In Sherman, Texas, just a mile down the road from what is being called the new semiconductor capital of America, is a small farm uninterested in technological advances. Instead, they are digging through the past, allowing nature to inform their ranching practices and adopting millennia-old principles of shepherding to produce clean, nutrient-dense proteins.

Prairie Farmstead is a small, family-owned ranch. On their North Texas prairie, they produce grass-fed, grass-finished beef, pastured pork, and pasture-raised eggs. Owners Molly and Chuck Trowbridge, along with Molly’s parents, the Blazos, don’t refer to themselves as ranchers, though. They prefer to be called regenerative grass farmers.

“We’re in the business of selling nutrient-dense proteins, right? But to do that, we are regenerative grass farmers first,” Chuck explains.

Regenerative agriculture is a set of farming and grazing practices focused on restoring the soil’s health and following principles of animal grazing that mimic those practiced naturally in the wild. It’s more than sustainability: at its core, the model is focused on returning to the natural state of the soil before industrial agriculture killed off the thriving symbiosis of plants, bacteria and animals.

By returning the land to its natural variety of grasses and unique microbiome, Prairie Farmstead is able to offer a more nutrient-rich diet for their herds, which translates to a cleaner, better tasting, more nutrient- dense protein. Land that is laden with its natural permaculture is also resilient to cyclical environmental pressures, such as drought and erosion, and therefore protects our food supply chain when conditions are less than ideal.

Pointing to the grass under his feet, Chuck says, “We try to use the nature here in Sherman— on this ground—as the context for all we do.” When the Trowbridges and their in-laws purchased the property seven years ago, they began by digging through history books and articles compiled by local historians and professors from nearby Austin College.

Uncovering 19th-century journal entries, they learned that historically, the land from Sherman to Bonham was Blackland Prairie and popular grazing ground for migrating bison herds.

“And so we’re trying to use the cattle to mimic, as much as possible, how those bison herds and other herbivores built this topsoil and the polyculture of prairie grasses that nourished them,” Chuck states.

Naturally grazing animals build healthy topsoil by breaking up earth’s hard crust and allowing seeds to germinate. Their hooves trample vegetation, turning it into mulch while pushing a variety of dormant seeds into the ground. Foraging prunes vegetation and the cattle’s gut acts like a living compost pile, churning out fertilizer that supports the unseen world of soil microbes.

Domesticated livestock can accomplish these same soil-building feats by using a method called adaptive grazing, the main component of transhumance.

A MILLENNIA-OLD TRADITION

Transhumance is the practice of moving livestock from one grazing ground to another, usually in a seasonal cycle. In nomadic cultures, shepherds lead this migration, ensuring their animals have access to water and the correct forage, and ensuring that pastured land has time to recover and reseed, growing next season’s meal. UNESCO calls transhumance one of the most sustainable and ecient ways to farm livestock and has dubbed the ancient droving traditions of the Mediterranean and Alps regions part of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.

The Prairie Farmstead cattle is shepherded daily between half-acre sections portioned out of a larger grazing pasture. When it’s time to move the cattle to a fresh foraging parcel, Chuck or a part-time ranch hand demarcates the new half-acre section using GPS coordinates on their phone, staking the new boundary with rope. e herd strategically moves at midday, when the carbohydrate content of the plants is at its peak, so the cattle receives the most nutrients from their meal.

Left to graze on the same land for too long, cattle will become picky, foraging on native plants that Chuck refers to as “ice cream” plants. They will continue to eat until the healthy, native plants are unable to reseed and regrow. The shallow-rooted, less nutrient-dense non-native plants (not the cows’ preferred choice) will proliferate, drowning out the native polyculture of grasses, creating an unnatural monoculture that opens the door to topsoil erosion.

It was less than a century ago that we suered the consequences of soil not rmly held down by strong roots. During the Dust Bowl, between 1930 and 1936, the Great Plains, including our Oklahoma neighbors, were destroyed in the worst man-aided ecological disaster in American history. Industrial tilling had killed native plants, decimating the topsoil, and turning lush pastures into nightmarish deserts: a dry, brown landscape where nothing (human, animal or plant) could thrive.

“I mean, not to over-dramatize, but I am worried about the ability for my great-grandchildren to have healthy food,” Molly says as she looks over at her young son playing alongside us as we walk the prairie. “There are only two paths, right? We [can] choose to become more like nature and go back and heal the land, understanding that sometimes we sacrifice our convenience; or we [can] become increasingly more synthetic and more separated from nature in order to survive as a species. There’s really only two paths, and I don’t want my kids—and their kids—on the latter.”

Genetics and establishing a legacy are vital in the ranch’s animal production. Establishing themselves as a 100-percent grass-fed, grass-finished beef operation means that not only has the protein on your plate never seen a “lick of grain,” Chuck says, but neither has the generation before them (and so on). After seven years, Prairie Farmstead herd genetics are established to thrive on North Texas native grass, which is the opposite of our North American beef industry that had bred cattle to do well in a feedlot setting.

Their first three years of farming were a test in patience. The regenerative practices returned little reward, as they waited for the permaculture of the land (native grasses thriving and non-native dying off) and genetics of the cattle (animals that thrive on North Texas native grasses) to fall in sync with one another. Year four was when things started to get interesting, which excited not just the Trowbridges but also a nearby group of agricultural researchers. Fifty-five miles north of Prairie Farmstead, across the Red River in Ardmore, Oklahoma, is Noble Research Institute, a 14,000-acre gathering ground of independent intellectuals and boots-on-the-ground ranchers dedicated to furthering regenerative stewardship and supporting regenerative farmers so they can be successful and turn a profit.

“Chuck Trowbridge and his family are putting soil health first and reaping the rewards,” says Hugh Aljoe, director of producer relations at Noble Research Institute. “As we’ve shifted our organization focus to regenerative ranching over the last two years, we’ve been able to learn from them—and others like them—[and] to see the tremendous benefits of this approach.”

Greenwashing isn’t a marketing tactic used at Prairie Farmstead. They only produce 100-percent grass-fed, grass-finished, pesticide-free protein. The pigs live out their days in a wooded area of the property, just as they would in nature, and also rotate through grazing paddocks. The chickens peck and run on grass every day, too.

You can purchase Prairie Farmstead beef, pork and eggs directly from their website or at the Celina Farmers Market. They also organize a community drop-off in Allen once a week, and their goods will be available at Heritage Butchery opening this fall in Denison.

If you’d like to see these regenerative practices in action, Prairie Farmstead offers bi-yearly tours. You’ll likely be in the company of other ranchers, some just starting and some experienced, looking to adopt the same practices and join the growing regenerative agriculture movement.

- prairiefarmstead.eatfromfarms.com

- IG: @prairiefarmstead

MELINDA ORTLEY is a Fine Art Photographer who believes that every image should stand alone as a work of art. Using the classic medium of film, her goal is to create vibrant, original images that go beyond her client's expectations, whether that client be a blushing bride, growing family, business owner or magazine editor. You can view her portfolio at www.melindamichelle.com.