Peering in the doorway, you would be hard-pressed to identify F-M 1410 as the leading edge of a food movement. Wooden crates, bottles of Texas olive oil, flats of sprouting plants and a washboard are among the clutter on its ramshackle shelves and tables. A speaker, amplifier and guitarish-looking instrument stand incongruously in

one corner. Boxes of mushrooms brood in a cold case, and a Kaffir lime tree huddles next to the window. The F-M 1410’s aging walls and cement floor are painted to resemble watermelon parts.

Then again, you wouldn’t take owner Tom Spicer for a culinary warrior. He isn’t a chef, although his sister, Susan Spicer, is a famous one who plies her craft in New Orleans. He doesn’t deconstruct or dabble in foam, although he’s on the speed-dial of plenty of chefs who do. If you catch him in the right mood, he might sauté up a mess o’ mushrooms on a hot plate, the better to fill his storefront with their earthy perfume. But Spicer’s not a kitchen man. He’s a dirt man.

“Tom is a horticultural genius,” says the Rosewood Mansion Restaurant’s former executive chef John Tesar. “He knows the Latin name for every herb or vegetable, and he’s a great source for anything in the world of agriculture, whether it’s knowledge or product. He’s my garden architect and co-conspirator.” Last year Spicer designed the

Mansion’s garden that produced the food featured on Tesar’s menu.

For a lot of area chefs, Spicer is the go-to guy for specialty produce, whether they are looking for Texas arugula, Louisiana chanterelles or

Peruvian baby lettuces.

“I know what a chef wants before they know,” Spicer says. “All my chefs are profiled.” He’s not bragging. He’s dead serious, as he ticks off the names of some of his clients: Sharon Hage (York Street), Dean Fearing, Scott Romano (Charlie Palmer at The Joule), Tony Zappola and Shannon Swindle (Craft), Avner Samuel, Julian Barsotti (Nonna), Grant Morgan (Dragonfly), Wayne Turner (Into the Glass) and Graham Dodds (Bolsa).

Spicer keeps what each chef wants inside his head: For one it’s purslane, for another, shelling beans, “specific ones that Texas doesn’t grow,” he says. “Petite lettuces are not being done locally…. They all like Louisiana citrus.” Whether he is recruiting local farmers to grow the special seeds he buys, cultivating high-demand items in the empty lot outside his back door or meeting a shipment of baby root vegetables from Baja at Dallas Love Field, Tom Spicer is a broker who’s as passionate as his chefs about well-cultivated produce and herbs.

Spiceman, as he’s sometimes called, is an enigma. At times, he appears as scattered as his F-M 1410 surroundings. At other times, it’s as if his mind is running two lengths ahead of everyone else’s. Ask him a simple question—“Is locally raised food better?”—and he will launch into a diatribe about a local grower whose produce he won’t buy because his farm is on top of a landfill.

It’s also as if he’s compelled by the gods of green to proselytize. When he wants you to understand the difference between wild Louisiana chanterelles, wild Oklahoma chanterelles and other chanterelles, he’ll point to the mushroom chart on his wall and show you how the delicate and lacy Louisiana mushrooms compare to the “large, fat and beefy” Oklahoma ones.

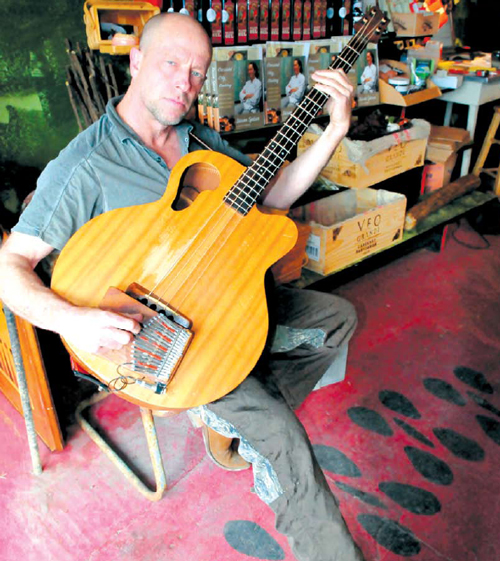

He’ll show you the bags of seeds he wants to share with growers or he’ll slice through the armor like skin of a pomelo so you can taste it. With a little sweet-talking after his afternoon glass of wine, he’ll fire up the kalimbass in the corner and play for you. That’s “kah-lembase,” as in a combination of bass guitar and kalimba.

Music and food are Spicer’s twin muses. On his Web site he calls them “ripe, delicious and sexy, like home-grown Creole tomatoes.” There was a time when music was the taproot and food, the clinging vine. Now it’s more like the plant tendrils have twined into his brain where music provides the cooling shade to keep his thoughts from overheating.

Born in Newport, R.I., where he lived for about a minute, Spicer is as New Orleans as Mardi Gras and gumbo. He grew up in the Crescent City and graduated from O. Perry Walker High School in Algiers. After a stint at the University of Southern Louisiana, he attended the elite Berklee College of Music in Boston. Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown invited him to join his band. He later toured as a bass man with, among others, Louisiana singer-songwriter Zachary Richard.

After Richard began gravitating toward acting, “I bounced around playing whatever I could in Lafayette,” says Spicer. He likes to say his love of music comes from his dad, while his love of the land (the dirt) comes from his mom, who taught him to garden. Connection to the soil runs deep in Spicer’s family: His great-grandfather was an English

horticulturist whom the Vanderbilts brought to New England in the early 1900s. But it was Richard’s girlfriend who introduced Spicer to the intoxication of French food in the early ‘80s, when the band was playing in Paris, France.

Spicer drifted toward produce gigs and Dallas, where he eventually became the assistant produce manager at Bluebonnet, one of the city’s seminal natural foods markets. “I was just a lettuce-and-herb guy at the time,” he says and credits the Bluebonnet produce manager with teaching him the retail side of the business. Spicer also was mentored by Dallas produce icon Joe Labarba, whom he says showed him how the Dallas Farmers Market worked. Then he was recruited by Golden Circle Farms,

a job that converged with Dallas’ first surge of interest in local sourcing. It was the 1980s, and regions across the country were taking Northern California’s lead. At the time, Dallas helped birth Southwestern cuisine.

“I was growing heirloom varieties [then],” Spicer says, “arugula, sprouts. I was selling baby arugula before California was selling it, four pounds for $5. We didn’t call it heirloom, the specific varieties. We didn’t call them micro-greens.” For those with memories long enough to remember Dallas’ first big ramp-up of fine dining, Spicer was supplying chefs like Stephan Pyles and his first Dallas incarnation, Routh Street Café; the Sardenian gang at Arcodoro and Pomodoro; Sfuzzi; and San Simeon with these produce specialties.

Spicer left Golden Circle in the early ‘90s and says he has been working to get a broker operation with a storefront like F-M 1410 ever since. In between, he rode personal ups and downs, which included a divorce—“depressing, depressing, depressing” – and the good luck to have bought an East Dallas house low and “sold it for stupid dollars.”

“One day I came down to see the Jimmy’s redo,” he says. Jimmy’s Food Store burned in 2004 and was rebuilt and reopened in 2005. A small space was available in an adjacent building. “I saw the ‘for lease’ sign, and I thought, ‘I have to make this happen,’ and I’m so glad I did.” In 2006, he signed the lease and in 2007, he opened for business. F-M 1410 alludes to the street address on Fitzhugh.

“F-M 1410 and Jimmy’s have a symbiotic relationship,” says Cole Kelley a former chef who hangs out and helps out at F-M 1410. “Anyone visiting Jimmy’s is likely to check out F-M 1410”, he says, “and F-M 1410 customers know that Jimmy’s is Italian central for Dallas.” There are those folks who poke their heads into F-M 1410, look around, puzzle and withdraw. There’s nothing there as far as they can see. But for those curious enough to risk entry, it’s a step into a unique universe where you won’t get away without a farmer’s-length conversation, a bag of something and perhaps even an impromptu kalimbass performance.

Seasoned by miles, Spicer recognizes that he’s made mistakes. He has also weathered fate’s blows and bad timing. This time around, he is determined to catch and ride the front of the locavore wave because he knows so much more than its green upstarts. He knows the chefs are his bread and butter, but his mission is to spread the gospel of great produce to anyone who will listen.

And despite his muddied rubber boots, his stream-of-consciousness style and his New Orleans Saints gimme cap, you believe him. The watermelon motif is a comfort but just now he’s licking his chops to spread a load of topsoil out back. “I’m just getting started,” he says with relish. And you come away thinking, “This Cajun means bid- ness.”

KIM PIERCE is a Dallas freelance writer and editor who’s covered farmers markets and the locavore scene for some 30 years, including continuing coverage at The Dallas Morning News. She came by this passion writing about food, health, nutrition and wine. She and her partner nurture a backyard garden (no chickens – yet) and support local producers and those who grow foods sustainably. Back in the day, she co-authored The Phytopia Cookbook and more recently helped a team of writers win a 2014 International Association of Culinary Professionals Cookbook Award for The Oxford Encyclopedia for Food and Drink in America.

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/

- Kim Piercehttps://www.edibledfw.com/author/kpierce/