Photo by Kurt Michael Friese

The following is an excerpt from the newly released Chasing Chiles: Hot Spots Along The Pepper Trail. The book traces the year-long journey of three pepper-loving gastronauts – Gary Paul Nabhan, an agroecologist, Kurt Michael Friese, a chef and Kraig Kraft, an ethnobotanist— who set out to find the real stories of America’s rarest heirloom chile varieties and learn about the changing climate from farmers and other people who live by the pepper and who, lately, have been adapting to shifting growing conditions and weather patterns.

Finding the Wildness of Chiles in Sonora

When we crossed the US–Mexico border into the estado de Sonora, we could feel something different in the landscape. It was especially visible along the roadsides, a feeling that was palpable in the dusty air. Less than half an hour south of Nogales, Arizona, we began to see dozens of street vendors on the edge of the highway, hawking their wares. There were fruit stands, ceviche and fish tacos in seafood carts, tin-roofed barbacoa huts, and all sorts of garish concrete and soapstone lawn ornaments clumped together. Amid all the runof- the-mill street food and tourist kitsch, we sensed that we might just discover something truly Sonoran.

Dozens of long strings of dried crimson peppers called chiles de sarta hung from the beams of the roadside stands, ready for making moles and enchilada sauces. Hidden among them were “recycled” containers used to harbor smaller but more potent peppers: old Coronita beer bottles and the familiar curvy Coca-Cola silhouette filled with homemade pickled wild green chiltepines. These were what we sought—little incendiary wild chiles, stuffed into old bottles like a chile Molotov cocktail and sold on the street.

They signaled to us that we had come into what the likes of Graham Greene and Carlos Fuentes have described as a truly different country—the Mexican borderlands. They are as distinct from the rest of Mexico as they are from the United States, for the borderlands have their own particular food, folklore, and musical traditions.

This is a country where a beef frank wrapped in bacon can become a “Sonoran hot dog”—with jalapeños, refried beans, crema, and fiery-hot salsa soaked into a soft-textured roll—and where ballads are sung about rebels and renegades, both those of the past like Pancho Villa and those of the present like the narcotraficantes of the Sinaloan drug cartel. It is a place where preservative-laden ketchup is frowned upon, and where freshly mashed salsas are nearly as common as water.

We were after the first and most curious of all the North American chile peppers, the chiltepin—the wild chile pepper of the arid subtropical sierras. It remains one of the true cultural icons of the desert borderlands, a quintessential place-based food, for it is still hand-harvested from the wild. Chiltepines are associated with human behaviors that are considered both sacred and profane. On the one hand, they are deified in an ancient Cora Indian creation story, and relied upon in Yaqui and Opata healing and purification rituals. On the other hand, they remain the favored spice in Sonoran cantinas and cathouses.

As to their own behavior, wild chiltepines are a fickle lot. They camouflage themselves and hide deep beneath the thorny canopies of hackberry bushes and mesquite trees, daring us to come after them and shed some blood. Exasperated, some Sonorans have tried to take them out of the wild and domesticate them. They have tried to cultivate them in drip-irrigated, laser-leveled fields, but they have had little luck taking the wildness out of this chile. In the US Southwest, the great demand among Chicanos for its unique flavor has created a market scarcity of the chiltepin. This has pushed prices up above sixty-five dollars per kilo in mercados on both sides of the border.

The difference in flavor and kick between the wild chiltepin and its domesticated brethren is much like the difference between Sonora and the rest of Mexico. Perhaps it is the potency of the desert itself that is expressed in the terroir of the chiltepin. Or maybe that potency is because it is truly a food of the borderland—verdaderamente de la frontera—a place so filled with environmental, political, and mythical juxtapositions that it has fire-forged certain unique characteristics in the Sonoran psyche. A disproportionate number of Mexico’s revolutionaries, rebels, presidents, dissidents, and saints have come from el estado de Sonora, a state of mind as much as a geographic one. No doubt, they were all eaters of the chiltepin, a food that the inimitable Dr. Andrew Weil once declared to be psychotropic. Perhaps in Sonora, you are really not what but where you eat.

The chiltepin is small but as fierce as the desert sun blazing on a summer day. Compared with other, bigger, but watered-down versions of peppers, it packs a terrific punch of pungency per unit ounce. And yet its fire quickly burns out; you are left with a lingering taste of minerals, the thirsty desert earth itself.

It is remarkable that the chiltepin remains one of few wild foods harvested in North America that grosses well over a million dollars in the international marketplace in a good year, for the chiltepin crop is very vulnerable to the vagaries of a harsh and variable climate. For us, Sonora’s stressed-out patches of wild peppers were the perfect place to make our first “landing” of our spice odyssey.

And so we careened off the highway pavement and into the desert’s dust, where a dozen roadside stands presented themselves on the edge of a Sonoran farming village named Tacícuri. That term is an ancient Pima Indian word for the wild pig-like peccaries known in the Sonoran Desert as javelina. Yes, there were still plenty of javelina, rattlesnakes, and Gila monsters in these parts, but that was not why we slid to a halt before this makeshift marketplace. It was the stunning sight of those six-foot-long strings of red-hot chile peppers that suggested chiltepines might be hidden nearby.

We piled out of our van (which we had long since christened the Spice Ship) and stood there amazed by all the paraphernalia, guaranteed to dazzle any spice lover. Not only were there dozens of fire-engine-red sartas strung with hundreds of long chile peppers, there were bottles and bags and baskets and bins full of other chiles as well: chiles del arbol, serrano chiles, jalapeños, and chiltepines. There was enough heat on that roadside to cause a nuclear summer if all of the fiery capsaicinoids in those fruits were ever ground and instantaneously let loose into the desert air.

“We have arrived,” Gary said to Kurt, who was on his maiden voyage into the deserts of Sonora. Gary had spent most of his “adulthood” in the Sonoran Desert—if in fact he had ever grown up at all—so he was serving as our host for this leg of our journey. However, Kraig was at the helm, for he had recently surveyed most of Mexico on his own, searching for the origins and domestication of chile peppers. Once out in the desert sun, Kraig took Kurt along to rattle off the local names for certain shapes, colors, and sizes that described particular varieties. As a seasoned chef, Kurt knew many of these variants, but by names somewhat different from those used in Sonora.

“Take one and grind it between your fingers,” Kraig demonstrated to Kurt, showing him how the locals put dried chiltepines in their food. “Just don’t rub your eyes afterward!” he added. “And remember to wash your hands before you visit the letrina,” Gary interjected, with a wry smile and an exaggerated gesture toward a nearby outhouse.

Kurt eyed the two of them with a look that said, I’m not the rookie you take me for. He had handled far too many peppers in his twenty years as a chef to be vulnerable to that kind of calamity anymore.

Of course, there was more for us to look at than just chiles: huge bins packed full of pomegranates and quinces; monstrous piles of striped cushaw squashes; and coolers full of local cheeses called queso asadero or queso cocido. The cornucopia of the desert stood before us in all its ragtag splendor.

CHASING CHILES:

HOT SPOTS ALONG THE PEPPER TRAIL

chelseagreen.com/bookstore/item/chasing_chiles:paperback

by KURT MICHAEL FRIESE, KRAIG KRAFT and GARY PAUL NABHAN

available now from Chelsea Green Publishing

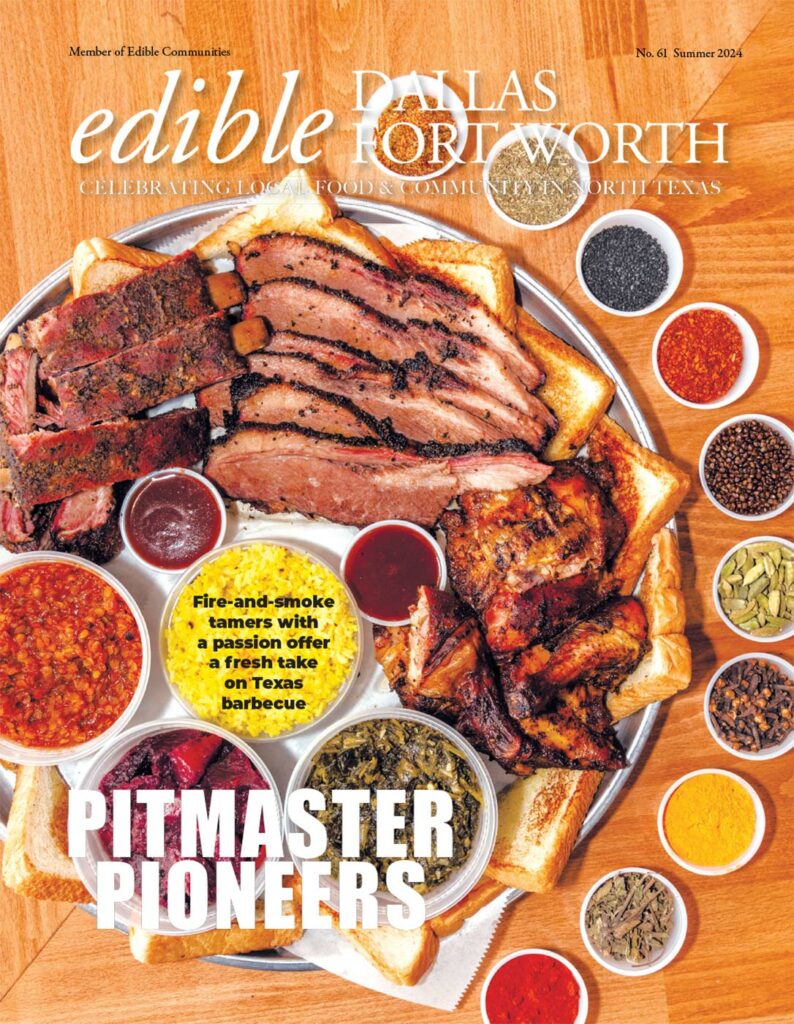

Edible Dallas & Fort Worth is a quarterly local foods magazine that promotes the abundance of local foods in Dallas, Fort Worth and 34 North Texas counties. We celebrate the family farmers, wine makers, food artisans, chefs and other food-related businesses for their dedication to using the highest quality, fresh, seasonal foods and ingredients.