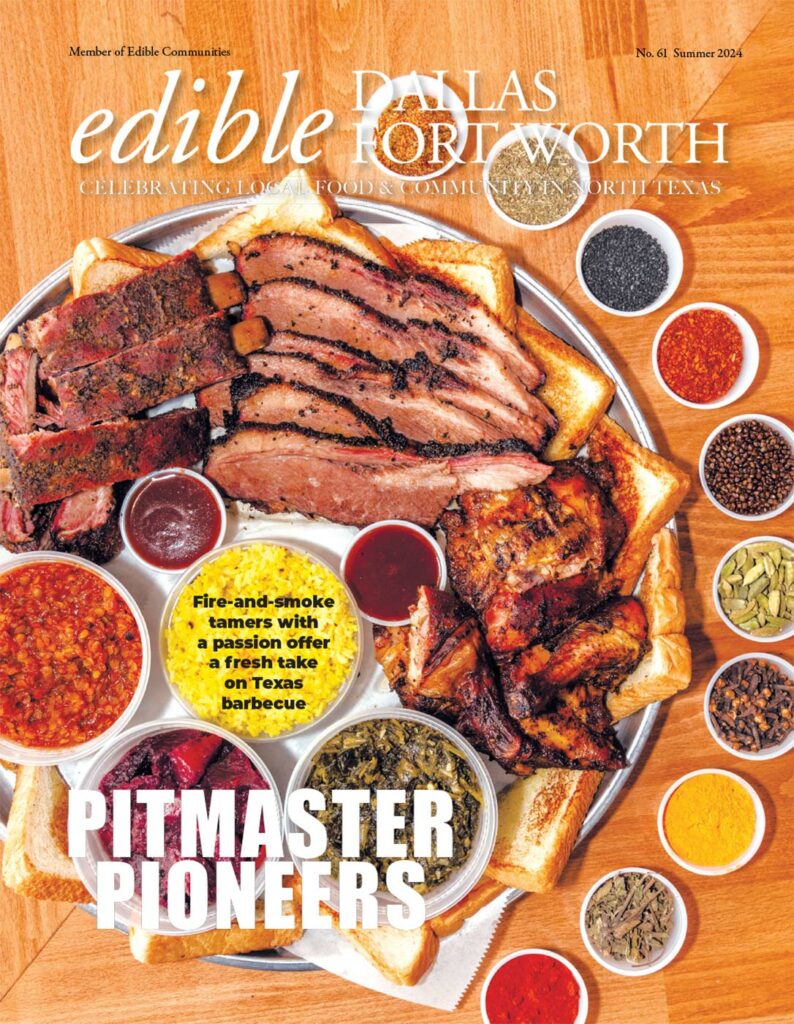

Photography by Kelly Yandell

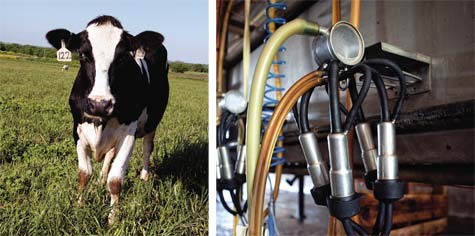

Nothing evokes an image of pastoral simplicity quite like a frosty glass of milk. In reality, the dairy business is a complex industry, contending with supply and demand and an array of variables that are not always easy to grasp. When considered as a monolithic industry, the state of milk in Texas is good. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Texas has risen to become the nation’s 6th ranked milk producer.

But the profile of the average Texas dairy farm is rapidly shifting from small and medium-sized farms to larger facilities with herds that number in the thousands. According to the Texas Association of Dairymen, the number of Texas dairy producers continues to drop, from approximately 1,100 in 2000 to around 500 in 2012. Over the same period, the number of dairy cows has increased 35%. Fewer farms, more cows.

Once the state’s leaders, Central and East Texas dairy farms have lost ground to bigger facilities in the High Plains. It is here—in the state’s western Panhandle—that eight of the ten top milk producing counties are now located. The number of dairy cows in that region increased nearly tenfold between 2000 and 2012. During the same period, most other Texas counties suffered a steep decline in both cows and farms. The average size of a High Plains dairy herd is over 2,700 cows with many facilities far exceeding that number.

CONVENTIONAL DAIRY IN TEXAS

A century ago, a glass of milk came from a family cow or the cow of a neighbor. Over the years, massive efficiencies were incorporated into the business to ensure that dairy farmers got their milk to market, and that people living many miles from the nearest dairy could obtain milk. Farmers created co-ops to pool their production. Co-ops negotiate with processors and wholesale buyers to sell the milk, and the farmers are all paid one price (per hundred pounds of milk).

The farm’s milk is pooled with that of other farms and delivered to a central processing facility. It is subject to quality standards, but it is all combined. The fluid milk and components are routinely shipped across state lines to larger facilities that package and brand the products for retail sales. Depending on the distributor, the milk you purchase could be coming from almost any state in the United States.

Dairy farmers are price takers, meaning they are paid after production at a price set by the markets. Spikes and dips abound but in 2009, during an economic downturn, prices fell well below the cost of production. Supply was high, demand fell and prices plummeted. This sustained period of low prices was cataclysmic for dairies nationwide. Many were forced to sell off cows or leave the business completely.

Given rising fuel and feed costs, the price paid to farmers is often unrealistically low. The recent drought has had a major impact. Heat distress can lower milk production in cows. Fans, evaporative coolers and other cooling devices are costly. The drought has made it very difficult to pasture feed cows and the high costs of constant irrigation are taxing. Farmers have had to look elsewhere for supplemental feed at increasing costs.

Economies of scale benefit large operations. Larger dairies with savvy financial staff, state-of-the-art technologies and lobbying abilities have an easier time weathering difficult years. Small dairies, unwilling to increase their herds or compromise their operations, are closing one by one. The economic loss to counties and the personal loss to families, many of whom have owned their farms for generations, are consequential. A 2006 Tarleton State University study of Erath County’s dairy industry estimated that the loss of a 1,000 head farm leads to a loss of 61 dairy-related jobs.

INDEPENDENT AND ORGANIC DAIRIES IN TEXAS

Alternatives to conventional milk exist. After struggling through the inevitable pricing cycles, some Texas dairies determined that allowing the price of milk to be set entirely by the processors was not a viable business model. Some have transitioned to organic or independent, or both.

There is an entire, albeit smaller, version of the conventional milk market for organics. Organic dairy certification is generally a threeyear process. But the price paid for organic milk is substantially higher, allowing organic farms to operate on a smaller scale.

Texas is also home to a growing number of independent dairies that have chosen to forgo traditional marketing routes and sell their milk in varied ways. Over the last few years, those dairies have spawned a groundswell of local milks, artisanal cheeses and yogurts that are highly sought-after by a growing consumer base.

Prior to 2002, Full Quiver Farm in Kemp, southeast of Dallas, milked 150 cows commercially. “We were going broke in the commercial dairy business,” says owner Mike Sams. “We had no choice.

We just had to do something else.” They sold down the herd to 50 cows. They do not sell the milk commercially, but instead sell raw milk from their farm store. They have also created a thriving cheese business, selling pasteurized milk cheeses and spreads to Whole Foods Market, Central Market and smaller high-end grocers like Bolsa Mercado, and to delivery services such as Greenling and Artizone. In addition, they sell their raw milk cheeses at the Dallas Farmers Market and at farmers markets in Austin. They have also begun selling their grass-fed beef, whey-fed pork and eggs at markets. “For a small producer,” remarked Sams, “this is the only way to go.”

The Sams family has nine children. Prior to their transformation into an independent dairy, their margins were so slim that none of the grown children were able to work on the farm. However, the business is now stable and profitable, and several of their grown children are part of the family business.

Alysha and Ben Godfrey of Sand Creek Farm and Dairy in Cameron began their farm as a conscious attempt to supply good food and a good life for their children. They have never sold milk in the conventional system and were the first Texas dairy licensed to sell raw milk directly to the public. Both have degrees from Texas A&M, in Scientific Nutrition and Agricultural Development, respectively. They have taken a very purposeful approach to raising healthy cows and selling wholesome food. They currently have 42 milking cows that are grass-fed on 170 acres. Alysha says that farmers have to educate consumers on “what good food really is,” and what it actually costs to produce it.

Currently, state regulations forbid consumers from buying raw milk anywhere except at the farm where it is produced. One of the unintended benefits of the law is that customers actually see how the cows are raised and witness the care that goes into their upkeep. The Godfreys, like most small independent dairy farmers, are vigilant about testing their animals frequently to make sure that what they are selling and feeding their own five children is the safest and highest quality milk possible.

Because of the decision to raise grass-fed dairy cows, the Godfreys are limited in the size of herd they can feed on their land. To maximize the health of the pastures and to diversify their offerings, they have also begun to rotate large vegetable gardens through the pastures. They also have three aquaponic greenhouses up and running, in which they grow lettuce, various greens and beets. While dairy is still the core of the family farm, this diversity of agriculture allows the Godfreys to maximize the potential of their acreage in a way that adds to the bottom line.

Even the largest of the independent milk producers in Texas are relatively small compared to the new commercial standards. Don Seale of County Line Farms, an independent organic milk producer in Earth, Texas near the New Mexico border, says their herd of 2,000 cows on 3,000 acres is diminutive compared to some of their neighbors. Their milk is sold at Green Grocer, Natural Grocers, Central Market, among many others. Seale is positive about the growth potential for independent dairy farmers, especially organic dairies.

“Some of our main goals are to not only gain exposure for our products throughout Texas but to provide information to consumers,” says Seale. “Milk is an ‘alive’ product that has to be handled differently. And it requires a great deal of dedication and work to maintain the high standards of our certified organic dairy.” The production for County Line’s herd is currently split between the private bottling and delivery to an organic co-op. The goal is to sustainably increase the amount of milk that can be dedicated to private bottling. Some independent farms devote their milk solely to the production of cheese and other value-added products. The Veldhuizens of Dublin, Texas, have created their line of farmstead cheese with raw milk from their select herd of predominately Jersey cows.

Other independents sell their premium milk directly to local artisanal cheese makers. The celebrated Mozzarella Company in Dallas uses milk sourced within 100 miles of Dallas. Eagle Mountain Farmhouse Cheese in Granbury sources milk from the organically raised herd of Brown Swiss cows owned by Mike and Debbie Moyers of Sandy Creek Farm in Bridgeport.

Marc Kuehl of Brazos Valley Cheese in Waco says, “We saw an opportunity to come in and work with farmers who have the same values that we have, and we pay them what their milk is worth.” It’s an issue of quality over quantity. All of the above companies have garnered national awards for their cheeses.

One commonality among all of the independent dairy families interviewed is that they believe that they are producing a truly superior product by working with fewer animals. They are feeding them grass and natural forage, relying very little or not at all on commercial grain. Some have chosen to forego organic certification, not only because of the cost and cumbersomeness of the process, but because they have personal relationships with their customers who visit farms and can see for themselves the way the cows are raised. Everyone emphasized that there is plenty of room in the independent milk and cheese market for dairies to switch to this model. As generously put by Mike Sams: “We were in trouble, and this has been the way it opened up for us. And, there is room for other people to do the same thing. I just like to see people succeed.”

Whether a dairy is conventional, independent, raw or organic— there’s something for everyone, and at every price level, in the Texas milk market. While conventional milk meets the needs of many, alternatives to mass-produced milk and associated products are holding their own, and the dairy farmers who produce these alternatives have found a growing market for their goods.

KELLY YANDELL is a writer and photographer based in Dallas. She has contributed to Edible Dallas & Fort Worth since 2011. Her website (themeaningofpie.com) celebrates practical dishes and comfort foods, while her photography portfolio can be found at kellyyandell.com. Kelly is an attorney and is the vice president of the Advisory Board of Foodways Texas, an organization founded by scholars, chefs, journalists, restaurateurs, farmers, ranchers, and other citizens of the state of Texas who have made it their mission to preserve, promote and celebrate the diverse food cultures of Texas.