PHOTOGRAPHY BY MARGARET WOLF

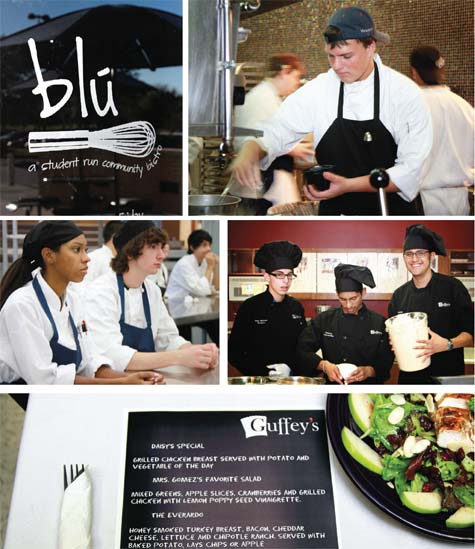

At Moisés E. Molina High School in Oak Cliff, students troop into Ann Guffey’s culinary arts class. “This is the guys’ table!” declares the victor of a quick round of Rock-Paper-Scissors. He triumphantly stakes a spot at one of the sanitized, stainless steel worktables that are part of Guffey’s push to professionalize the program she took over four years ago. On the far wall, second-hand appliances donated by a local restaurant bring this teaching kitchen one step closer to becoming commercial grade.

A chalkboard-fronted cabinet displays hand-written vocabulary: sous chef, garde manger, certification, apprentice, fine dining, business plan. When her students graduate, “they’re qualified to be a kitchen manager somewhere,” Guffey says. Of the four culinary arts programs in Dallas Independent School District [DISD], Molina is the only one without a commercial kitchen. It is also the only one to have garnered a win in last year’s Dallas Regional ProStart Culinary and Restaurant Manager Competition. This success has galvanized even more interest in a growing program.

In another part of the Metroplex, Allen High School has a high-end practicum kitchen that puts many restaurants to shame. It’s an example of how far programs have come in recent years. On a Wednesday morning, Jordan Swim’s culinary arts class is a blur of white chef jackets. Steam escapes from under stockpot lids as teams of juniors work on béchamel and vegetable stock, executing the most perfect, professional dice I’ve ever seen. Behind them, the senior team preps for the rush of lunchtime guests that will descend on Blú, their elegant, student-run restaurant, which is open to faculty and the greater public. They’ve roasted turkey for the house club sandwich, made brown-butter cakes and prepared a batch of tortilla soup using their homemade chicken stock and a recipe from the Mansion on Turtle Creek.

As recently as seven years ago, Allen offered a simple Home Economics course run out of a classroom that resembled a home kitchen. “The idea was ‘Everybody cooks,” says Karen Bradley, Career and Technical Education Principal. “People didn’t view it as a career – they were learning to cook at home.”

Then came the shift to a career-oriented approach, accelerated by the state’s widespread adoption of the ProStart curriculum, a flexible but systematic, pre-professional approach for students at the high-school level. Currently, 35 high schools in the Dallas area use the curriculum as a foundation. In Allen, out went the Home Ec model. In came Robot Coupes and hefty volumes of Gisslen’s Professional Cooking and Professional Baking textbooks.

“We teach methods,” Swim says. This means a technique-based foundation similar to that of any culinary academy. Swim’s juniors are in the midst of a unit on the mother sauces of classical French cuisine that will take them through Hollandaise, Béarnaise, and Mornaise. Elyse Simchik, the leader of Allen’s “Iron Chef” competition team, says, “There were so many basic things I didn’t think mattered.” Like stocks and sauces. “And all the different cuts!” Her goal is to attend the Culinary Institute of America [CIA], whose Hyde Park, New York campus recently began offering credit to Allen graduates. Many graduates of Dallas’s ProStart programs enroll at schools like the CIA or the local culinary programs at El Centro and Collin County Community College.

Culinary Arts Students, Molina High School

Culinary Arts Students, Molina High School

Training high-school students as future chefs means teaching them the precision, pace and discipline of a professional kitchen. “Some thrive on it,” says Swim, “And some realize they don’t.” Kayla Baker, one of his juniors, calls time checks and helps another group by whisking a dirty pot into the sink for final cleanup. “My personality is leadership,” she says. “I like the rush of it.”

The programs also connect students to a larger story, awakening them to the possibilities of food—its potential to express culture and unleash creativity. “A lot of them have never been to a restaurant before, and if they have, it’s fast food,” Guffey says of her students, a majority of whom are Hispanic. “Many have never eaten anything but Mexican food at their home.”

Natural curiosity is an ally as Guffey introduces them to new ingredients. Students may ask her to buy an artichoke at the store, simply because they want to try it. They, in turn, introduce her to mole or posole brought from home. One year, a student invited her over for her mother’s chile rellenos as a thank-you at the end of the year. “They’re so loving,” Guffey says. “They’ll take you in.” These are the intangible rewards of Guffey’s job at the intersection of food and community.

Guffey’s strategy is to ground her students in what they know and have them add a twist. The winning meal her students created for the regional ProStart competition featured familiar motifs, transformed: an upscale quesadilla, a poached pear accompanied by a cinnamon tortilla and caramel sauce. “I’d never had students create recipes before,” Guffey says. “I was just so proud of how hard they worked, how dedicated they were, their teamwork.”

The students at Allen represent a very different demographic but arrive with a similarly limited knowledge base. “They grew up eating Sloppy Joes and nachos,” Swim says. “[Coming in,] they don’t have a great food heritage.” The challenge is to teach students basic principles that will allow them to unlock the poetry in food – an idea at the heart of classical French method.

“First, get them to understand that they can take a crate of vegetables and make a meal . . . take raw foods and cook them and create something,” Swim says. The goal? Reach a point where, “when you smell celery and carrots and onions cooking, you think about where that can take you.” In the case of junior Javier Grimaldo, that might mean chicken Cordon Bleu, a dish he was inspired to tackle on his own after seeing the senior team try it.

By the end of the school year, the Allen students will create mini restaurants in teams — “pop-up” operations which they can infuse with their own touches. The creative process starts once the skills are in place, Swim says. First come skills and trust and “then they can go for it.”

Two days a week, Guffey’s students run a café open to faculty, with a menu that has grown in five years from one daily dish to an expanded selection and lunch rushes of 60 diners. Ideally, Guffey would like her students to know more about the farms and ranches that grow the foods they serve. But she, like Swim, is often limited to buying from large, district-approved distributors. At Allen, Swim has secured permission to grow herbs like rosemary and thyme in an edible landscape.Blú’s fall menu featured North Texas honey and squash and zucchini from a farm in Alvarado. His students compost their food scraps and are involved with the local Future Farmers of America chapter. Still, he’d like more connections with farmers.

Awakening students to the real world of food can be painful. Watching the film Food, Inc. last year was a shock for many of Guffey’s students, who reeled at its depictions of the agro-industrial food production system. “It never crossed their minds,” she says. For many, awareness brought a sense of urgency and sadness. “A lot of them feel helpless,” she says. “They don’t have any control.” Food choices in their homes are dictated by “what their parents can afford.” So Guffey talks with them about what they can control: getting involved with meal planning, replacing a few ingredients. And she keeps them focused on the future they’re shaping. “If you go into the food industry and you open a restaurant, are you going to keep these things in mind?” she asks them. “It’s not just about learning how to cook a piece of chicken. They’re learning a lot about life. And they’re realizing they can impact a lot of people. They’re the future of this industry,” she says.

An understanding of the vital role these students play is precisely what mobilizes the local professional community’s support. The Greater Dallas Restaurant Association [GDRA] hosts regular round-table sessions for ProStart instructors and helps pair them with mentors in the industry.

“We made this a priority for our association about ten years ago. We said we had to commit to support these schools,” says Tracey Evers, Executive Director of the GDRA. “You think of an organization like this and you think lobbyists. But this is really the feel-good element. It gets the whole restaurant community involved and excited. You see the faces of the kids, and it’s really something tangible.” Last year, the GDRA awarded $82,000 in scholarships to support students pursuing further studies in a culinary field. When DISD could not provide funds to send Molina’s regional-winning team to the state round in Austin, the GDRA raised money that funded uniforms.

Guffey also appreciates the support she’s received from individual restaurateurs eager to teach knife skills, help craft seasonal menus or set up externships. “It’s in the industry. It’s in their blood,” she says. “They’re excited about the future.”

The students give back to the community, too. When I visited Molina, they were busy developing healthy snack recipes for a cookbook that Medical City Hospital will be distributing to elementary school children. The goal is to make eating fruits and vegetables appealing and fun.

“I can’t tell you how genius they are. They know what kids like,” says Ryan Eason, program director for Medical City Children’s Hospital’s kids teaching kids program.

Recently, these and other accomplishments have gained the attention of DISD Board members. The district has proposed hiring a designer to help Guffey create a facility fit to house a premier program. “They told me to dream big,” she says. The goal is to secure funding through an upcoming bond measure, like the one that helped Allen make its culinary imprint.

With their restaurant the bustling center of a larger community, Swim says his students feel connected. When National Football League representatives came to tour the school’s new stadium, they ate at Blú. The nearby senior citizen center sends a shuttle every week. The students cater for events at the performing arts center. “That’s our story here: a community-minded approach.”

This is the story Guffey and Swim want their students to feel connected to and claimed by. Swim says he loves to watch “how food becomes important to them and [to] the rhythms of their life. . . . They’re creating something for people that lives on.”

EVE HILL-AGNUS teaches English and journalism and is a freelance writer based in Dallas. She earned degrees in English and Education from Stanford University. Her work has appeared in the Dallas Morning News, D Magazine, and the journal Food, Culture & Society. She remains a contributing Food & Wine columnist for the Los Altos Town Crier, the Bay-Area newspaper where she stumbled into journalism by writing food articles during grad school. Her French-American background and childhood spent in France fuel her enduring love for French food and its history. She is also obsessed with goats and cheese.