Organic Life At Windy Hill

Photograpy by Richard Adams

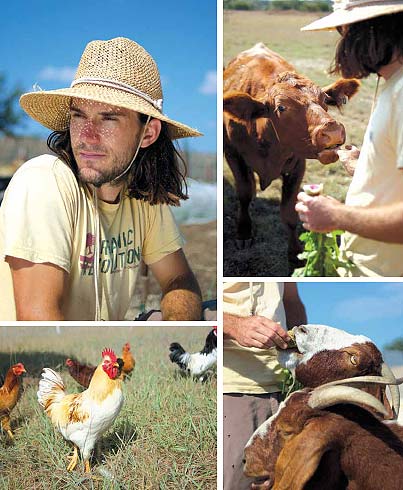

The unpaved road off FM 590 coils through fields of dried grass, past sleepy cattle towards a pastoral ranch house. At the road’s end stands Ty Wolosin, the 26-year-old organic farmer who runs Windy Hill Farm. Beside him rest two Anatolian Shepherd dogs, Kate and Kadir. From behind the largest of the beasts, trots out a very confident chestnut chicken.

“Yeah, that’s Tootles,” says Ty. “She thinks she’s a dog.”

Wearing paint-speckled white denim jeans and a t-shirt, Ty plops on his straw hat and draws the string tightly to his chin. His shoulder-length brown hair peeks out from the sides.

“I always wear my hat,” says Ty. “Last time that I didn’t, I came home looking like Rudolph.”

It is here, at Windy Hill Farm in Comanche that Ty walked away from society to devote his life to organic farming, sustainable living and the humane treatment of livestock.

His mother and stepfather, Jan and James Williams, live with Ty on the farm and assist him on weekends and evenings. Jan, a retired real estate agent, runs the household, and James works for AT&T.

Six years ago, they bought the 100-acre farm, bringing tools and supplies from their previous livestock ranch in Goldthwaite. Ty remembers driving up to the farm on the first of June 2008 in his Budget rental truck. He spent his first five months alone while his parents worked overseas on assignment for AT&T. Since then, he’s built up two lush organic gardens and two chicken coops. He also maintains small herds of goats and Red Brangus cattle that surround the gardens and house. Ty says he envisions a farm that grows less in size, but more in reputation and influence.

“Rather than me expand and buy out the farmer next door, I’d rather do it cooperatively,” says Ty. “I don’t think of myself as a venture capitalist, and I don’t know that I want to be.” While Ty is not a certified organic farmer, he is Certified Naturally Grown. He says the costly organic certification is necessary for a retailer, but a small farmer can rely on his good reputation and working relationships.

A giant pronged John Deere tractor emerges from the shed like a charging bull. It gores and then lifts a 1400-pound barrel of hay, the weekly supper for the crimson cattle. As the machine rumbles off the road over crunching grass, dozens of grasshoppers leap out of the way from under dried cow pies. A jackrabbit shoots by, looping the tractor once before ducking into one of the many cedar bushes that speckle the rolling land.

“They’re water hogs,” says Ty of the scruffy trees. He plans to clear the land of them.

It hasn’t rained at Windy Hill Farm in almost two months. The fields are parched and sparse, and the small pond is reduced to a crater. It has lost 20 feet in radius, a new record. The topic of rain is popular, and the chances for rain are checked throughout the day. “It’s time for Ty to do his rain dance,” says Jan.

As a child in Taos, New Mexico, Ty often worked in his parents’ garden, but only if a form of bribery was involved. A diagnosis of thyroid cancer at age 19 changed his worldview. He switched from fast food to a vegan diet as he underwent treatment. With the cancer in complete remission, Ty continues his healthy habits, but has reintroduced dairy and meat as long as he knows exactly where the animal products originated.

After earning his bachelor’s degree in geography at Texas State, Ty attended the University of Montana, where he earned his master’s in geography. After a brief internship at a desk job, Ty quickly realized the regular nine-to-five work week could never work for him. “I could never live solely for the weekend,” says Ty. “I couldn’t live like that; I can’t live like that.”

In 2009, Ty started the weekly three-hour drive to Dallas, rotating Saturdays between the Dallas Farmers Market and the White Rock Local Market. Fridays are devoted to market preparation.

Salad greens are cut, washed and bagged. Goat meat and beef are readied, if back from the processor. His cornucopia of local, organic options sell out every time. On Saturday, he wakes up at 3 a.m., loads the truck and heads to Dallas. Within the first hour, all of the salad greens and eggs are gone. “I’ve never seen people like something more in my life,” says Ty. He can’t always keep up with the demand. Drop-offs are also made to area restaurants such as Bolsa, Smoke and the Spiral Diner.

Though most of his days and nights are consumed with farm chores, he tends bar twice a week at the Turtle Enoteca in Brownwood. There he creates cocktails made with ingredients from his farm and takes charge of selecting which beers and fine wines to stock. Tuesday evenings, he teaches an entry level geography course at Howard Payne University. It provides an opportunity to socialize and earn a steady extra income.

If he hadn’t been presented with the farming opportunity, Ty sees himself living a transient lifestyle. His world travels already span 30 countries over five continents. He’s climbed Mount Kilimanjaro, and he speaks conversational Spanish. Now, Ty brings the world to him by housing volunteers through World Wide Opportunities on Organic Farms, an exchange program where farmers offer accommodations and meals in exchange for work. So far, 20 percent of Ty’s volunteers have been international. In August, Sebastian Imhof left Switzerland to visit various organic farms in the United States. His stay with Ty in September grew from the usual two weeks to six weeks. Currently, Sebastian is trying to arrange his visa so he can return next year.

Ty describes himself as a non-religious, outspoken, workaholic. He says he is also not a morning person. At 8 a.m., late by farming standards, he steps out with his stepfather to move the portable chicken coop. A jack rabbit has lodged itself in the electric chicken fence. They untangle it, but the rabbit is bloody and mangled. James runs inside and grabs his gun.

“That’s just part of it,” Ty sighs. “There is always something in the morning you don’t expect.”

The rest of the morning is spent weeding. Ty pulls back a white mesh material, revealing rows of perfectly lined arugula, broccoli, radishes and watermelons. Thousands of tiny, clover-like weeds called henbits surround the plants like an advancing army. Every single one must be pulled. The soil releases the weeds easily with a soft suck. They plunk as they drop into his orange bucket.

Suck, plunk, suck, plunk. The wind and goats chime in as the baritone, and the sparrows supply the soprano. The weeding becomes a rhythmic, hypnotic melody.

He doesn’t listen to music as he works. He learns from listening to the bugs and the way a bird’s call changes when a hawk is near. Every afternoon jets from Carswell Air Force Base in Fort Worth screech violently across the cloudless sky. It’s an unwelcome daily reminder of the outside world. Ty says his relationship with nature and the Earth can’t be described as spiritual. It’s more of a deep connection and an intricate understanding of how things work, like weather patterns.

“Fire ants,” yelps Ty. He retrieves a can of dried molasses and pours it over the mound. “That should take care of them,” he says, dusting off his hands. For bug deterrents, Ty utilizes what he refers to as the Homeland Security for Windy Hill Farm. Based on the severity of the infestation, Ty ranks six possible responses that are organic and tiered for their destructiveness.

He attributes a lot of his gardening success to careful planning and the technique of double digging. Two six-inch layers of soil are loosened, and the top layer is replaced with a nitrogen rich source such as mulch or bat guano. It’s a slow moving, arduous mission, but once it is completed, it will remain effective for two years. Full days are devoted to double digging, even during the hottest summer months.

It’s rare that Ty gets a free day or evening away from the farm. Occasionally, he slips away to Austin to catch a music show, but he must always make the two-hour drive home afterwards. While Ty is burdened by this tremendous entity that’s forever dependent on him, he possesses the spirit of a man who is truly free. He answers to no one but nature and himself.

On an organic farm, life slows down. The weeding process is slow, the digging is slow, even the dogs lope along with ease. Ty points to the sunset. “You know that it’s nearing wintertime when the setting sun shifts closer to the mesa,” he says as he surveys his land. “There we go, sunrise to sunset.” Smiling, he stomps up the steps to the ranch house door and hangs up his straw hat.

VALERIE GORDON GARCIA is Texas-based freelance writer. She received her masters in journalism from the Mayborn School of Journalism and her bachelors in journalism from the University of North Texas. She worked her way through college as a manager of an organic health food store where she developed a knowledge of and an appreciation for organic and natural foods. She lives in Dallas with her husband Tommy and her cats Ernie and Neko.

- This author does not have any more posts.