How two Fort Worth friends built a malthouse connecting farmers, brewers and distillers

The barley is trucked to Fort Worth, where it’s malted in small batches.

PHOTOS BY MEDA KESSLER

It pretty much started over a beer,” Chase Leftwich says, laughing. It’s a fitting origin story for TexMalt, the Fort Worth malthouse he cofounded with his friend Austin Schumacher. The two met while working in the oil and gas industry but spent their spare time home-brewing and visiting craft breweries. Somewhere between brewing experiments and barroom conversations, a simple question bubbled up that functioned as a catalyst: Why isn’t anyone malting Texas grain for Texas beer?

At the time, in 2015, nearly all malted barley used by local breweries came from the northern United States, Canada or Europe. “Me being from Lubbock, Texas, and a lot of farming [happening] up there, we just thought, why can’t we grow this in Texas for our Texas brewers?” Leftwich recalls.

That question became a challenge and an opportunity: to create malt that tasted of terroir. In 2017, they moved into the historic OB Macaroni building in south Fort Worth (later expanding to larger facilities) and began proving that Texas soil could shape the taste of Texas beer.

Texas barley: An agricultural challenge Barley isn’t a crop that naturally thrives in Texas heat. It prefers cooler, milder springs. But with determination—and assiduous trial and error—TexMalt partnered with farmers in the Panhandle, where cooler temperatures and reliable irrigation gave the grain a fighting chance. “Nobody had really grown barley in Texas since Prohibition,” Leftwich says.

“When we started, we didn’t even know what varieties to use,” Schumacher recalls. “We had to pick some being grown in the Carolinas at a similar latitude and hope for the best.” A decade later, their farmer partners have fine-tuned the process, and seed companies offer more resources.

“We can talk to them, and they can help from the seed agronomics side. That was not the case 10 years ago,” Schumacher adds. “Now, we don’t lose sleep over it. We’ve gone from having no malt-grade barley grown in Texas to matching the quality you would expect from any boutique malting operation across North America.”

SMALL-BATCH SCIENCE MEETS CRAFT

Malting—the controlled germination and drying of grain that makes brewing and distilling possible—is both science and art.

Inside TexMalt’s Fort Worth facility, barley is soaked, sprouted and kilned with precision. Small changes in temperature or airflow can transform flavor, aroma and color.

“We do everything per batch,” Schumacher explains. “It’s singleorigin barley, malted in one facility at one time.” Unlike their competition—large international companies—they do not blend to achieve uniformity. Steep duration, germination parameters and kiln temperatures play a role in bringing out the special character in each grain.

Leftwich likens it to baking. “There’s certain chemical reactions happening in the grain at all times that you can manipulate.”

Through steps often eliminated by larger malthouses, they’re able to coax a deep, rich malt flavor out of their Munich, for instance, that “you really can’t get out of big, commercial company-style Munich,” Leftwich says.

A COLLABORATION BETWEEN FIELD AND GLASS

Brewers and distillers depend on consistency, so TexMalt works It’s not like growing other grains or even barley for other uses. “We’re looking for a different set of parameters and specifications to meet the raw-grain quality we need to even be able to bring it into the malthouse,” Leftwich says. Consistent extract ratios, for example, require that protein levels remain within a certain range—around 10 percent for brewers and slightly more for distillers.

The farmers hone the agronomic aspects of crop rotation and soil dynamics; the malters translate that work into a result that local brewers and distillers can use. “We let the farmers be the experts in farming,” Leftwich says. “And we know what we need and how we need to operate inside the malthouse.”

Often, their farmers are innovators who have a hankering to do more than sell wheat to the local grain elevator. And the duo is open about the results. “Our crops got a little stressed this year, so our extract is a little lower,” they might tell a brewer. “So the brewer might need to use a little more malt to hit the effciency they need to hit,” Leftwich says. It’s all part of working with Texas agriculture.

Barley is stored in silos at the Fort Worth facility as well as on their farm. PHOTOS COURTESY OF TEXMALT

Grain goes through the grinding process in large metal bins resembling open-top shipping containers. Some of the processed grain is stored in large containers.

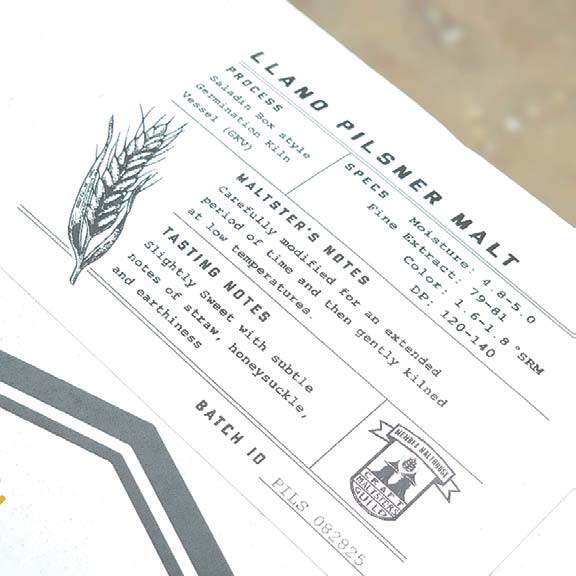

That collaboration has yielded remarkable results. When Fort Worth’s Maple Branch Craft Brewery brewed its pilsner with TexMalt barley, the only ingredient they changed was the malt —and the difference was striking: it added a unique taste of honeysuckle. “Seeing a brewer taste it and say, ‘this is what Texas barley tastes like,’ that’s the reward,” Schumacher says. Ten years ago, that wouldn’t have been possible.

FLAVOR YOU CAN TASTE

TexMalt offers brewers and distillers something authentic. “Yeah, I mean, there’s nuance to it,” Leftwich says about the often-overlooked foundation of beer and whiskey. “We can experiment with these different grains and profiles that just weren’t even available previously.”

“When everything’s shipped in from Canada or Europe, the only thing local about the beer is the water,” Schumacher adds. “Being able to source the largest ingredient—the malt—right here in Texas is pretty cool.”

TexMalt has also made a name for its malted colored corns — red, white and blue — something few others offer. Before, brewers relied on flaked maize, a neutral ingredient. Malted corn, Schumacher explains, adds “incredibly different flavor impacts” to light beers and lagers.

Currently, TexMalt has an even split between distillers and breweries in terms of quantity sold. One of their biggest customers, Still Austin Whiskey Co., uses 100 percent Texas grain. “And it is totally different from anything you’ll find in Kentucky,” Leftwich says.

GROWING A TEXAS MOVEMENT

TexMalt now produces about 3 million pounds of malt a year— still a small fraction of the 80 million pounds Texas breweries and distilleries use annually. But for Leftwich and Schumacher, the goalisn’t to dominate; it’s to deepen the state’s flavor identity.

“We play a small role in the overall malt usage, but we’d like more breweries to be able to use Texas grain,” Leftwich says. “As an arrogant Texan, if it’s made in Texas, why not use Texas agriculture?”

The two co-founders have watched a decade of progress in craft malting worldwide, from new seed research to the formation of a tightknit community that shares ideas like brewers once did in the early craft -beer movement. “It’s incredibly collaborative,” Schumacher says.

“Everyone’s focused on quality, not quantity. We’re all just trying to make better malt.”

From colleagues in their industry, “we’ve gotten a nod of, ‘OK, they’ve figured it out.’ And that’s really cool,” Leftwich says. In the next two to three years, TexMalt’s founders imagine they won’t have the choice but to discuss expansion: It’s a good problem to have.

The TexMalt test kitchen has a countertop still that allows staff and clients to taste test the flavoring process. PHOTO COURTESY OF TEXMALT

As they look ahead, the pair hope to bring more farms into the fold and inspire more brewers and distillers to embrace Texas-grown ingredients.

For them, the reward outweighs any struggle. “Being the missing link between a local farm and a brewery or distillery has been really fun and rewarding,” Schumacher says. “As consumers become more and more educated, they want to taste local flavor.” And being able to tell that story, from the farm to the malthouse to the brewery to the pint is deeply satisfying.

“As far as Texas goes, we’re the biggest resource for [agronomics honing], and we had to figure it out on our own,” Leftwich says, with the duo’s characteristic blend of guts and humility. “It just takes time. Fortunately, it didn’t take too much time.”

TEXMALT

Learn more about the Fort Worth-based company through its website and social media.

www.texmalt.com

www.instagram.com/texmalt

www.facebook.com/texmalt

EVE HILL-AGNUS teaches English and journalism and is a freelance writer based in Dallas. She earned degrees in English and Education from Stanford University. Her work has appeared in the Dallas Morning News, D Magazine, and the journal Food, Culture & Society. She remains a contributing Food & Wine columnist for the Los Altos Town Crier, the Bay-Area newspaper where she stumbled into journalism by writing food articles during grad school. Her French-American background and childhood spent in France fuel her enduring love for French food and its history. She is also obsessed with goats and cheese.

- Eve Hill-Agnus

- Eve Hill-Agnus

- Eve Hill-Agnus

- Eve Hill-Agnus

- Eve Hill-Agnus

- Eve Hill-Agnus

- Eve Hill-Agnus

- Eve Hill-Agnus